|

International Transfer Pricing

By Mark R. Martin

Introduction

Transfer pricing has become an important international taxation issue for both tax administrations and taxpayers.1 Transfer pricing issues arise with respect to the movement of goods, intangibles, services, or capital across international borders, where there is value or benefit on either side of the transaction. Generally, transfer pricing looks at whether the price charged for a transaction in goods, services, capital or intellectual property between affiliated enterprises (related parties) is “arm’s length.” Section 482 of the United States Internal Revenue Code provides that related party transactions must be priced at “arm’s length,”2 and this standard is applied by most countries.

The purpose of the arm’s length standard is that related parties generally care about their global profit as a group and may not care where the profit is reported. Accordingly, such parties may be motivated to report more profit in a jurisdiction with a lower tax rate or where they could utilize a loss. Tax authorities apply the arm’s length standard to prevent arbitrary shifting of income by requiring related party transactions to be priced as if they were not related parties. Thus, tax authorities use the arm’s length standard to prevent tax base erosion.

This article provides a general background of U.S. pricing law and highlights transfer pricing issues for taxpayers and government authorities.

A. Role of Transfer Pricing in International Taxation

The essential transfer pricing principles in all jurisdictions are generally similar under the umbrella of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)3 Transfer Pricing Guidelines and Model Income Tax Convention. Deviations in a few jurisdictions are eliminated through treaty-based, Competent Authority negotiation procedures, or other means of pressuring such countries to conform to international standards.

If the taxpayer is doing business in two or more treaty countries, it has assumed taxpaying obligations in each jurisdiction. Transfer pricing is a three-way contest pitting tax administration against tax administration, in the case of bilateral treaty-country matters, with the taxpayer often occupying the position of stakeholder in the middle. Transfer pricing allocates income between jurisdictions. In this three-way contest, each party has its own concerns.

Each country touched by the operations of a multinational enterprise will want to tax an appropriate portion of the profits earned by operations within its borders. Thus, tax administrations of most developed and developing countries use transfer pricing as a tax base defense mechanism. On the other hand, multinational enterprises are concerned with defending their transfer pricing policies, often designed to facilitate the tax planning paradigm of the enterprise. From the standpoint of most multinational enterprises, taxes are simply a cost of doing business, which, like all costs, must be minimized to prevent a competitor from obtaining a competitive advantage from a lower tax rate.

Internal Revenue Code Section 482

The purpose of Section 482 is to ensure that taxpayers clearly reflect income attributable to intra-party, or controlled, transactions and to prevent tax avoidance for such transactions.4 In determining the true taxable income of a controlled taxpayer, the standard is that of a taxpayer dealing at arm’s length with an uncontrolled taxpayer, meaning that the transaction would be the same as one between uncontrolled taxpayers under the same circumstances. Because identical transactions are rare, comparable transactions under comparable cir-cumstances are considered.5

A. Transfer Pricing Methodology

The regulations for Section 482 prescribe specified methodologies for determining the arm’s length terms for the transfer of tangible property, intangible property, and capital between controlled taxpayers.6 The regulations also address services transactions, although they do not contain specified methodologies for pricing service transactions. In addition, the regulations allow unspecified pricing methodologies where the specified methodologies do not apply.7 The taxpayer must use the method that provides the most reliable measure of an arm’s length result.8 While there are no priority rules for determining the best method, the regulations indicate under which circumstances particular methods are likely to be most reliable.

1. Tangible Property

With regard to transfers of tangible property, there are five specified methods: (1) the comparable uncontrolled price method; (2) the resale price method; (3) the cost plus method; (4) the comparable profits method; and (5) the profit split method.9

a. Comparable Uncontrolled Price Method

The comparable uncontrolled price (“CUP”) method evaluates whether the amount charged in a controlled transaction is arm’s length by reference to the amount charged in a comparable uncontrolled transaction.10 The taxpayer must establish that the products, contractual terms, and economic conditions of the controlled transaction bear a close similarity to the uncontrolled transaction.11

b. Resale Price Method

The resale price method measures an arm’s length price by subtracting the appropriate gross profit from the applicable resale price for property involved in the controlled transaction.12 The appropriate gross profit is computed by multiplying the applicable resale price by the gross profit margin earned in comparable uncontrolled transactions.13

c. Cost Plus Method

The cost plus method is ordinarily used in situations involving the manufacture, assembly, or other production of goods sold to related parties.14 This method adds the appropriate gross profit to the controlled taxpayer’s costs of production in the transaction.15 The appropriate gross profit is computed by multiplying the controlled taxpayer’s cost of producing the property by the gross profit markup, expressed as a percentage of cost, earned in comparable uncontrolled transactions.16

d. Comparable Profits Method

The comparable profits method (“CPM”) evaluates whether a transfer price is arm’s length based on objective measures of profitability (profit level indicators) derived from uncontrolled taxpayers that engage in similar business activities under similar circumstances.17 The arm’s length result is determined by the amount of profit that the tested party would have earned if its profit level indicator equaled an uncontrolled comparable.18

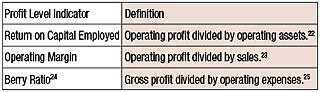

Profit level indicators are ratios that measure relationships between profits and costs or resources employed.19 The Treasury Regulations specify a number of profit level indicators that can be used in applying the CPM method. Whether the use of a particular profit level indicator is appropriate depends on the facts and circumstances of the case, including the nature of the tested party’s activities, the reliability of the available data for uncontrolled comparables, and the extent to which the profit level indicator is likely to produce a reliable measure of the income that the tested party would have earned had it dealt with the controlled taxpayer at arm’s length.20 Once an appropriate profit level indicator is selected, the taxpayer should assemble profit level indicator data for the taxable year at issue and the preceding two years.21 The Treasury Regulations describe the following profit level indicators:

In addition, the Treasury Regulations provide that “other profit level indicators” not described therein may be used if they provide reliable measures of the income that the tested party would have earned had it dealt at arm’s length.26

e. Profit Split Method

The profit split method evaluates the allocation of operating profit or loss in a controlled transaction to determine whether the allocation reflects the relative value of each controlled party’s contribution to the combined operating profit or loss.27 The profit allocated to any particular member of a controlled group is not necessarily limited to the total operating profit of the group from the relevant business activity; accordingly, in a given year, one member of the group may earn a profit while another incurs a loss.28

Profit split methods are used most often when both sides of the controlled transactions own valuable “nonroutine intangibles,” meaning intangibles for which there are no reliable comparables.29 If all valuable nonroutine intangibles were owned by only one side, the other side’s contributions could be reliably benchmarked using the CPM.

The Treasury Regulations endorse two forms of profit split: (i) the “comparable” profit split and (ii) the “residual” profit split.30 Under the comparable profit split, the controlled parties’ total profits are split based on how parties in comparable uncontrolled arrangements would split profits.31 Under the residual profit split, the controlled parties are each assigned a return for routine functions.32 Any remaining profit or loss is considered nonroutine intangibles and is split between the parties “based upon the relative value of their contributions of intangible property to the relevant business activity that was not accounted for as a routine contribution.”33

2. Intangible Property

a. Generally

The three specified methods for determining an arm’s length amount in a controlled transfer of intangible property are: (i) the comparable uncontrolled transaction method; (ii) the CPM discussed above; and (iii) the profit split method discussed above.34

b. Comparable Uncontrolled Transaction Method

The comparable uncontrolled transaction (“CUT”) method evaluates whether the amount charged for a controlled transfer of intangible property was arm’s length as compared to a comparable uncontrolled transaction.35 This method requires that the controlled and uncontrolled transactions involve either the same intangible property or comparable intangible property.36 To be comparable, both intangibles must (i) be used in connection with similar products or processes within the same general industry or market, and (ii) have similar profit potential.37 Determining whether intangibles have similar profit potential involves examining the net present value of the benefits to be realized from the intangibles.38 Absent such net present value evidence, all of the facts and circumstances surrounding the transfer must be examined, including the terms of the transfer (e.g., exclusive or non-exclusive) and the stage of development of the intangible.39

c. Cost Sharing Agreements

Another issue is the treatment of intangibles developed from the joint efforts of two or more controlled parties. A cost-sharing arrangement is an agreement between two or more controlled parties to share the costs and risks of a research and development project for an agreed upon scope in exchange for a specified interest in the project’s results.40 Since the participants in the arrangement jointly own the developed technology, there typically is no royalty obligation for a participant to use it. For example, affiliates in the U.S., France, and Japan might jointly develop technology that each affiliate will exploit in its respective regional market. A cost-sharing agreement can avoid royalties for the jointly developed technology, since joint owners exploit the technology. A cost-sharing agreement, however, must be “qualified” as set out in Treasury Regulation § 1.482-7(b).41 A key requirement is that participants share development costs in proportion to their shares of reasonably anticipated benefits from exploitation of the intangible.42

An interesting issue in the cost-sharing context is how participants that contribute pre-existing intangibles should be compensated by other participants for the “buy-in” to such intangibles. The Treasury Regulations provide that a controlled participant that makes intangible property available to a qualified cost-sharing arrangement will be treated as having transferred interests in such property to the other controlled participants, and such other controlled participants must make buy-in payments to the party that transfers the intangible property to the cost sharing arrangement.43 Proposed cost sharing regulations issued in August of 2005 adopt the “investor model” for buy-in payments to cost sharing arrangements, which are referred to as “external contributions” under the proposed regulations. Very generally, the “investor model” provides that external contributions to cost sharing arrangements should encompass separate payments for current product generation and for developing future product generations.44

3. Loans or Advances

If one member of a group of controlled entities makes a loan or advance directly or indirectly to another member of such group, without interest, or at a rate that is not equal to an arm’s length interest rate, the IRS may make appropriate allocations to reflect an arm’s length rate for the use of such loan or advance.45

4. Services

Although the current Treasury Regulations under Section 482 do not set forth specific methods for determining the arm’s length charge for related party service transactions,46 recently promulgated Proposed Treasury Regulations describe six methods to price such transactions.47 Those are: (1) the comparable uncontrolled services price method, (2) the gross services margin method, (3) the cost of services plus method, (4) the simplified cost-based method, (5) the comparable profits method, and (6) the profit split method.48 These proposed regulations, promulgated in September 2003, reflect the IRS’ and Treasury’s initial effort to update the services regulations originally promulgated in 1968.

As a general rule, the IRS may make adjustments under Section 482 where one member of a group of controlled entities performs marketing, managerial, administrative, technical, or other services for the benefit of another member of the group for less than an arm’s length charge.49 However, if the benefit conferred upon the service recipient is so indirect or remote that an unrelated party would not have charged for the service, then the IRS may not make an adjustment.50

If the service recipient in a related party service transaction receives a benefit from services provided, the service provider must be compensated on an arm’s length basis.51 For this purpose, the Treasury Regulations define an arm’s length charge as the amount that was charged or would have been charged for the same or similar services in independent transactions involving unrelated parties in similar circumstances.52 However, where the services are “non-integral,” the arm’s length price may be limited to reimbursement of the direct and indirect costs incurred for the service without markup.53

As noted above, the Treasury Department has proposed regulations governing related party service transactions.54 In developing these Regulations, the Treasury focused on transactions that look like services, but actually are transfers of intangibles or service transactions with significant intangibles used by the service provider.55

B. Determination of the “Best Method”

The Treasury Regulations contain no strict hierarchy of methods, and particular transaction types are not assigned to particular methods. Instead, the Regulations prescribe a more flexible, “best method” approach, considering the method that provides the most reliable measure of an arm’s length result.56 Usually, data based on results of unrelated party transactions provide the most objective basis for determining an arm’s length price.57 In such cases, reliability is a function of (i) the degree of comparability between the controlled transactions or taxpayers and the uncontrolled ones, (ii) the quality of the data and assumptions in the analysis, and (iii) the sensitivity of the results to deficiencies in the data and assumptions.58 Factors affecting comparability include the industry, the functions performed, the risks assumed, contractual terms, the relevant market and market level, and other considerations.59 Moreover, if there is a material difference between the controlled and uncontrolled transactions, adjustments must be made if it is possible to determine the effect of such differences on prices or profits with sufficient accuracy to improve the results’ reliability.60 Thus, the best method arises from the most reliable combination of transfer pricing methodology, comparables, and adjustments.

C. Arm’s Length Range

In some cases, a pricing method will produce a single result that is the most reliable measure of arm’s length.61 In other cases, a method may produce several results from which a range of reliable results may be derived (an “arm’s length range”), and a taxpayer whose results fall within the arm’s length range will not be subject to adjustment.62

An arm’s length range usually is derived by considering a set of two or more uncontrolled transactions of similar comparability and reliability.63 If these comparables are of high quality,64 then the arm’s length range includes the results of all of the comparables (from the least to the greatest).65 If, however, the comparables are of lesser quality, the reliability of the analysis must be increased by adjusting the range through application of valid statistical methods.66 The analysis’ reliability increases when statistical methods establish a range of results in which the limits of the range will be determined such that there is a 75 percent probability of a result falling above the lower end of the range and 75 percent probability of a result falling below the upper end of the range.67 The “interquartile range” (i.e., the range from the 25th to the 75th percentile) generally provides an acceptable measure of this range.68

If the results of a controlled transaction fall outside the arm’s length range, the IRS may make allocations that adjust the controlled taxpayer’s result to any point within the arm’s length range.69 If the interquartile range determines the arm’s length range, such adjustment will ordinarily be the median (i.e., the 50th percentile) of the results.70

Section 482 Penalty

One of the most important elements of the current transfer-pricing environment is the potentially draconian penalty in Sections 6662(e) and (h), which can impose a 20 to 40 percent penalty on related tax underpayments. A helpful exception to the transfer-pricing penalty is the “reasonable documentation exclusion,” which, in effect, excludes transactions covered by “contemporaneous documentation” of transfer pricing policies and procedures.71 The documentation requirement is met if the taxpayer “maintains sufficient documentation to establish that [it] reasonably concluded that, given the available data and the applicable pricing methods, the method (and its application of that method) provided the most reliable measure of an arm’s length result” under the best method rule and provides that documentation to the Internal Revenue Service within 30 days of a request.72 Generally, such documentation must exist when the return is filed.73

The Importance of Transfer Pricing to Tax Executives

A. Background

The world of international transfer pricing and taxation is in a state of rather amazing evolution in 2006. The tax authorities in a broad range of countries have become well attuned to tax base defense via aggressive transfer pricing examination and the assertion of proposed adjustments based on clever theories, including profit split methodologies used by other tax authorities on their home country-based multinational enterprises. The current environment includes the following elements:

1. Contemporaneous Transfer Pricing Documentation

As discussed above, an exception to the U.S. transfer pricing penalty is available to taxpayers who prepare contemporaneous documentation of their transfer pricing arrangements and provide such documentation to the IRS. Similarly, over 50 countries now require contemporaneous transfer pricing documentation.74 Thus, compliance with these documentation requirements has become a critical issue for tax executives of multinational enterprises.75

2. Sarbanes-Oxley Compliance.

Even if multinational enterprises have contemporaneous transfer pricing documentation in place, such enterprises may have Sarbanes-Oxley compliance problems if internal controls are not in place to ensure that the documentation was followed.76 Advanced pricing agree-ments with tax authorities (discussed below) may be used to show that the company has internal controls in place for transfer pricing.

3. Increased IRS Examination of Transfer Pricing.

Until recently, the IRS did not rigorously examine transfer pricing arrangements of U.S. multinational enterprises. This has changed in recent years. The IRS Large and Mid-Size Business Division (LMSB) stated in January of 2003 that it was undertaking a review of existing practices to ensure that the U.S. tax base is not being depleted by inadequate application of the arm’s-length standards of Section 482 (the “LMSB Initiative”).77 Transfer pricing is the top priority in the LMSB Initiative, undertaken to assess the handling of transfer pricing issues and controversies. In addition, the U.S. Congress is critical of the IRS’ failure to enforce U.S. tax base defense through transfer pricing examinations.78 Moreover, the LMSB Initiative provides that a penalty cannot be waived without International Territory Manager concurrence.

B. Advance Pricing Agreements

1. Background

Since 1991, the IRS has offered taxpayers, through the Advance Pricing Agreement (“APA”) program, the op-portunity to reach an agreement, before filing a tax return, on the appropriate transfer pricing method (“TPM”) for related party transactions.79 The APA Program has completed over 500 APAs and is the leading program of its kind. Many treaty partners have developed APA procedures modeled after the U.S. Program.

The APA Program was borne out of the desire to resolve transfer pricing issues fairly and efficiently. There is a fundamental perception that fairness cannot be obtained in having the IRS’ examination team – which is responsible for making audit adjustments -- in charge of a voluntary dispute resolution process. Placing the APA Program in the Office of Associate Chief Counsel (International) gave the Program both the appearance of independence and actual independence from the examination function of LMSB. Over the years, the APA Program has succeeded and gained credibility with taxpayers as an honest broker in reaching agreement on difficult transfer pricing issues. The APA Program has jurisdiction to resolve transfer pricing issues under Section 482, IRS regulations, and relevant income tax treaties to which the United States is a party.80

2. Nature of APAs

An APA resolves transfer pricing issues on a prospective basis and is a collaborative process between taxpayers and the IRS to resolve these issues under the arm’s length standard. A “bilateral” APA is an agreement between the IRS and a taxpayer on specified related party transactions coupled with an agreement between the United States and a treaty partner that the TPMs on such transactions are correct.81 Although the IRS encourages taxpayer to seek bilateral APAs, it may execute an APA with a taxpayer without reaching agreement with a foreign tax authority (i.e., a “unilateral” APA). A unilateral APA binds the taxpayer and the IRS, but does not prevent foreign tax administrations from taking different positions on the appropriate TPM for a transaction.

Because an APA resolves issues prospectively, the filing of an APA request does not suspend any examination or other enforcement proceedings. However, in appropriate cases, a TPM agreed to in an APA may be applied to tax years prior to those covered by the APA (“rollback”). In this context, IRS Examination has jurisdiction to determine whether the rollback will be applied.82 Similarly, if a rollback is requested in connection with a bilateral APA, the rollback will be handled in the Competent Authority process.

3. The APA Process

To begin the APA process, a taxpayer must submit an application for an APA, together with a user fee.83 However, the taxpayer can anonymously solicit the informal views of the APA program. Taxpayers must file the appropriate user fee on or before the due date of the tax return for the first taxable year that the taxpayer proposes to be covered by the APA. Many taxpayers file a user fee first and then follow up with a full application later. The IRS team considering the APA request generally will include a team leader, an economist, an international examiner, LMSB field counsel and, in a bilateral case, a U.S. Competent Authority Analyst who leads discussions with the treaty partner.

4. APAs and Sarbanes-Oxley

As noted above, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act requires procedures to identify material transfer pricing exposures.84 An APA is an agreement with one or more tax authorities, so exposure on the transactions covered appears to be minimal. Moreover, annual reports must be filed with the IRS (and typically other tax authorities in a bi-lateral APA) to establish that the APA has been applied by the taxpayer. This annual reporting requirement establishes a procedure (i.e., filing of an annual report) that should be helpful in establishing that controls are in place to monitor transfer pricing arrangements.

Conclusion

Transfer pricing involves all transfers of value between affiliated entities (whether in connection with the transfer of tangible or intangible property, the rendition of services or the transfer of capital). Since every country touched by the extended operations of a multinational enterprise will want to ensure that such enterprise is paying an appropriate amount of tax in their country, tax executives for multinational enterprises must be vigilant in determining that such related party transfers of value are priced on an arm’s length basis.

Mark R. Martin is a partner in the Houston office of Gardere Wynne Sewell LLP. Martin’s practice focuses on transfer pricing and international tax matters for multi-national enterprises, including assisting clients in negotiating advance pricing agreements, handling competent authority cases, representing clients in transfer pricing controversies and

assisting clients in transfer pricing planning matters.

Endnotes

1. See O’Haver, “Transfer Pricing: A Critical Issue for Multinational Corporations,” Tax Analysts Doc. No. 2006-5915 (May 4, 2006). 2. IRC. § 482. Unless otherwise indicated, Section references are to the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, as amended. 3. Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. See http://www.oecd.org. 4. Treas. Reg. § 1.482-1(a). 5. Treas. Reg. § 1.482-1(b). 6. Treas. Reg. §§ 1.482-3 (tangible property), 1.482-4 (intangible property) and 1.482-2(a) (capital). 7. E.g., Treas. Reg. § 1.482-3(e)(1). 8. Treas. Reg. § 1.482-1(b). 9. Treas. Reg. § 1.482-3(a). 10. Treas. Reg. § 1.482-3(b). 11. Treas. Reg. § 1.482-3(b)(2)(ii). 12. Treas. Reg. § 1.482-3(c)(2). 13. Treas. Reg. § 1.482-3(c)(2)(iii). 14. Treas. Reg. § 1.482-3(d)(1). 15. Treas. Reg. § 1.482-3(d)(2)(i). 16. Treas. Reg. § 1.482-3(d)(2)(ii). 17. Treas. Reg. § 1.482-5(a). 18. Treas. Reg. § 1.482-5(b)(1). 19. Treas. Reg. § 1.482-5(b)(4). 20. Id. 21. Id. 22. Treas. Reg. § 1.482-5(b)(4)(i). 23. Treas. Reg. § 1.482-5(b)(4)(ii). 24. Named after Professor Charles Berry, who used the Berry Ratio when serving as an expert witness in E.I. DuPont de Nemours & Co. v. U.S., 608 F.2d 445 (Ct. Cl. 1979). The Treas. Regs. do not use the term “Berry Ratio,” but the term is widely used in practice. 25. Treas. Reg. § 1.482-5(b)(4)(ii). 26. Id. 27. Treas. Reg. § 1.482-6(a). 28. Treas. Reg. § 1.482-6(b). 29. Treas. Reg. § 1.482-6(c)(3)(i)(B). 30. Treas. Reg. § 1.482-6(c). 31. Treas. Reg. § 1.482-6(c)(2). 32. Treas. Reg. § 1.482-6(c)(3). 33. Id. For an example of the application of the profit split method, see Treasury Regulation § 1.482-6(c)(3)(iii). 34. Treas. Reg. § 1.482-4(a). 35. Treas. Reg. § 1.482-4(c). 36. Treas. Reg. § 1.482-4(c)(2)(3)(iii). 37. Id. 38. Id. 39. Id. For examples of the CUT method, see Treasury Regulation § 1.482-4(c)(4). 40. Treas. Reg. § 1.482-7(a). 41. The IRS and Treasury Department issued proposed cost-sharing regulations on August 22, 2005. 70 Fed. Reg. 51116. See Daily Tax Report No. 162, L-3 (BNA August 23, 2005). 42. Treas. Reg. § 1.482-7(a). 43. Treas. Reg. § 1.482-7(g)(1). 44. Prop. Reg. §§ 1.482-7(b)(3) and (c). 45. Treas. Reg. § 1.482-2(a)(1). 46. See Treas. Reg. § 1.482-2(b); see also Preamble to Proposed Regulations addressing related party service transactions promulgated on September 5, 2003. 68 Fed. Reg. 53448. The current Treasury Regulations also do not explicitly incorporate the “best method rule,” although the best method rule would be applicable to service transactions under the Proposed Treasury Regulations. Prop. Treas. Reg. § 1.482-9(a)(1) (2003). 47. Prop. Treas. Reg. § 1.482-9(a) (2003). 48. Id. 49. Treas. Reg. §1.482-2(b)(1). 50. Treas. Reg. § 1.482-2(b)(2)(i). 51. Treas. Reg. §1.482-2(b)(1). 52. Treas. Reg. § 1.482-2(b)(3). 53. Id. See also Treas. Reg. § 1.482-2(b)(4). 54. Bell, U.S. Treasury to Retain Features of Intercompany Service Regs. That Minimize Taxpayer Disputes, Tax Analysts Doc. No. 2003-2616 (Feb. 3, 2003). 55. Id. 56. Treas. Reg. § 1.482-1(c)(1). 57. Treas. Reg. § 1.482-1(c)(2). 58. Id. 59. Treas. Reg. § 1.482-1(d)(3). 60. Treas. Reg. § 1.482-1(d)(2). 61. Treas. Reg. § 1.482-1(e)(1). 62. Id. 63. Treas. Reg. § 1.482-1(e)(2)(i). 64. See Treas. Reg. § 1.482-1(e)(2)(iii)(A). 65. Treas. Reg. § 1.482-1(e)(2)(iii)(A). 66. Treas. Reg. § 1.482-1(e)(2)(iii)(B). 67. Id. 68. Id. 69. Treas. Reg. § 1.482-1(e)(3). 70. Id. 71. Treas. Reg. § 1.6662-6(d). 72. Treas. Reg. § 1.6662-6(d)(2)(iii)(A). 73. Id. 74. Hammer, Lowell, Burge & Levey, “International Transfer Pricing: OECD Guidelines,” Chap. 14 (WG&L Sept. 2005). 75. See O’Haver, “Transfer Pricing: A Critical Issue for Multinational Corporations,” Tax Analysts Doc. No. 2006-5915 (May 4, 2006). 76. Lowell, Briger & Martin, “U.S. International Transfer Pricing,” ¶ 10.03[5][c][iv] (WG&L Jan. 2006). 77. Tax Analyst Doc. 2003-3767. 78. 206 BNA Daily Tax Reporter G-3 (Oct. 26, 2004). 79. Rev. Proc. 2006-9, 2006-2 I.R.B. 278 (Dec. 19, 2005). 80. Id. 81. Id. 82. Id. 83. Id. 84. Lowell, Briger & Martin, “U.S. International Transfer Pricing,” ¶ 10.03[5][c][iv] (WG&L Jan. 2006).

Text is punctuated without italics.

< BACK TO TOP >

|