|

The ‘Eyes of Taxes

are Upon You’

By William E. Junell.

On May 23, 2006, Governor Rick Perry completed the enactment of what some have called the most far-reaching tax legislation in Texas history.1 These new taxes are principally intended to better fund public education in Texas. The purpose of this article is to provide some historical background and an overview of the legislation that has been passed. Its focus is particularly toward services organizations such as law firms.

Why Did Texas Have a Constitutional Problem?

Article VIII, Section 1-E of the Texas Constitution provides that the state may not impose a statewide ad valorem tax.2 In Carrolton-Farmers Branch Independent School Dist. vs. Edgewood Independent School Dist.3, the Texas Supreme Court held that “an ad valorem tax is a state tax when it is imposed directly by the state or when the state so completely controls the levy, assessment and disbursement of revenues, either directly or indirectly, that the authority employed is without meaningful discretion.”

The Texas Constitution further provides that “a general diffusion of knowledge being essential to the preservation of the liberties and rights of the people, it shall be the duty of the Legislature . . . to establish and make suitable provision for the support and maintenance of an efficient system of public free schools.”4 “Efficiency” must be both qualitative and quantitative (or financial). And more recently, the Supreme Court in Neely v. West Orange Cove Consolidated School Dist.,5 concluded that the statewide cap on property tax rates and the Legislature’s duty to meet its minimum constitution requirements combined to eliminate meaningful discretion in funding. That is, by setting the educational floor and a financial ceiling, tax rates were forced to the top, and a de facto state property tax - which is prohibited under Article VIII of the Texas Constitution - was created.

What is the Educational Problem and Why?

According to the Supreme Court in Neeley v. West Orange-Cove,6 Texas has over 4.3 million children in public schools, and the number continues to increase each year. More than half are considered economically disadvantaged. It is estimated that the annual cost of public education in Texas exceeds $30 billion and that the cost per student is about $7,150 a year. Nationally, Texas ranks 40th in the average per pupil expenditures in fiscal year 2005. It ranks 33rd in teacher salaries.7 Historically, there have been three principle sources of financing for public education in Texas. First, over half of the cost has been funded by ad valorem taxes collected by local independent school districts. Nearly 40 percent of the cost is provided by the state from general revenues and approximately 9 percent is contributed by the federal government.

While there are over 1,000 independent school districts, a fourth of the student population is actually educated in only 12 districts located in only 7 counties. Half of the students are educated in 45 of the 1,000 districts. The largest district is the Houston Independent School District, which has over 200,000 students. Two-thirds of the school districts have fewer than 1,200 students and almost a fourth have fewer than 350 students.8 In short, there is wide disparity between the size of the various school districts in this state.

Inefficiency in education had become readily apparent. Some districts have higher property values and fewer students, while others have lower property values and more students. This has placed unfair tax burdens on different populations and inevitably resulted in an inefficient system of statewide education in Texas.

Senate Bill 79, enacted in 1993, established Texas’ present public school finance system. This legislation capped property tax rates at $1.50 per $100 valuation. This “Robin Hood Bill” further provided that property tax revenue could be taken from rich districts and given to poor districts so as to supplement the latter’s maintenance and operations expenses. The purpose was to try to equalize access to revenue among disparate districts.

The Neeley case was originally filed in April of 2001 by a number of school districts that contended that the maximum tax rate had effectively become a state ad valorem tax prohibited by the Texas Constitution. Other intervening districts claimed that public school finance in Texas was inefficient, inadequate and unsuitable and thus violated Article VII, Section 1 of the Constitution. In Neeley, the court held that local ad valorem taxes had effectively become a state ad valorem tax in violation of Article VIII, Section 1-E, that the public school finance system in Texas was inadequate and violated Article VII, Section 1, and that the funding of school facilities was inefficient in violation of Article VII, Section 1.10 An injunction was entered, and the state was denied the right to continue distributing funds under the current school finance system unless and until the Constitutional violations were remedied. The injunction was stayed until October 1, 2005 to give the Legislature reasonable time to cure the deficiencies. The Supreme Court extended this deadline until June 1, 2006.

Where Does the State Currently Get its Money?

In 2005, the state of Texas collected approximately $29.8 billion in tax revenue. Over half of the tax revenue comes from sales taxes collected on the sale of goods. The existing franchise tax provides about 3.3 percent, or almost $2.2 billion, of this revenue.11 It is expected that the revised franchise tax will increase this to approximately $12 billion. By comparison, only seven states rely on a general business tax for a larger share of the state’s revenue.

What was Wrong with the Existing Business Tax in Texas?

Previously, corporations and limited liability companies organized and doing business in Texas were subject to the Texas franchise tax. General and limited partnerships were exempt.12 For franchise tax purposes, each qualifying company was annually assessed the greater of .25 percent of net taxable capital or 4.5 percent of net taxable earned surplus. Taxable capital included paid-in capital and retained earnings. Earned surplus closely followed federal taxable income, with limited adjustments. No tax was due if the computed tax was less than $100. More importantly, there was no minimum tax.13 The franchise tax in Texas raised nearly $2.2 billion in 2005.

The nature of the Texas franchise tax, not surprisingly, encouraged businesses to organize and operate in a tax advantageous way. As a result, some have estimated that only 1 one in 16 businesses actually paid this tax. The Legislature believed that it should close the “loopholes” in its business tax and thus create a broader and a fairer tax. By implementing the new margin tax, the state proposes to spread the financial burden of paying for education in Texas across a broader cross section of the Texas economy so that public schools will have a more stable and predictable source of revenue.

The Texas Tax Reform Commission and the Special Session

After several failed attempts by the Legislature to address these issues, Governor Rick Perry appointed the Texas Tax Reform Commission to devise and recommend reforms that would provide a long term source of school funding. This Commission, chaired by former Comptroller, John Sharp, held statewide public hearings. In March of 2006, the Commission issued a report that proposed substantial modifications to the Texas franchise tax.14

With this report in hand and working against the Supreme Court’s June 1, 2006 deadline, the Governor called the Legislature back into special session to consider the proposals of the Sharp Commission and to develop and adopt a new school finance and tax reform bill. In May, 2006, the Legislature passed five bills.15

- House Bill 1 requires each local school district to reduce its property tax rate for school maintenance and operations from $1.50 to $1.00 per $100 valuation, with a hard statutory cap of $1.30 per $100 in valuation. Governor Perry says this tax cut represents approximately $15.7 billion in property tax relief over the next three years and will help lower property taxes up to 33 percent. Furthermore, HB 1 dedicates new tax revenues to salary increases for teachers in the amount of $2,000 per year plus performance driven benefits.

- House Bill 2 dedicates funds raised by the increased taxes, plus approximately $2.4 billion from the state’s general surplus, to property tax relief. The state currently has a surplus of $8.2 billion.

- House Bill 3 adopts a gross margin tax on many Texas businesses. This tax is expected to raise $53.4 billion and ultimately provide over 50 percent of the cost of education in Texas. It is estimated that state spending on education will increase by approximately $1.6 billion or about 4 percent per year.

- House Bill 4 provides that used car auto sales taxes are to be based on a standard (“blue book”) value rather than the reported value by the owner. This tax is expected to raise $70 million.

- House Bill 5 raises the state tax on a pack of cigarettes from $.41 to $1.00. This tax is expected to raise $700 million.

But Isn’t there a Constitutional Prohibition Against a State Income Tax in Texas?

Yes. In 1993, Texas Speaker of the House Bob Bullock orchestrated the enactment of an amendment to the Texas Constitution that provides that any “tax on the net income of natural persons, including a person’s share of partnership and unincorporated association income” requires statewide voter approval.16 The new margin tax raises at least two fundamental questions: is it a tax on “net income” and, if so, is it a tax on “natural persons”? The bill attempts to avoid these potential pitfalls by, first, taxing a calculated margin (gross income less some but not all expenses) instead of “net income” and, second, by taxing the computed “margin” of a business entity rather than an individual. Texas Comptroller Carole Keeton Strayhorn has asked the Attorney General for a formal opinion on this subject.

Will the Tax Meet the Financial Requirements of Our Public School System?

The business tax is not without controversy on this point and has raised a number of serious questions. There is on-going debate as to whether this tax actually will produce the funds necessary to offset the property tax cuts imposed by House Bill 1 and still meet the Supreme Court’s educational requirements. Some authorities have suggested that the revenue growth assumptions are overstated and that the tax will likely fall short of projections. According to Comptroller Strayhorn: “(the lawmakers) passed the largest tax increase in Texas history and it does not balance. They thought they were raising $12 billion in revenue. I ran the numbers and found they raised about $8 billion.”17 The uncertainty may well lie in certain growth and other assumptions that have been made, and the accuracy of those assumptions may not be known until tax collections occur.

What are Other Lawyers Saying?

Certainly since “tort reform,” it has become fashionable to attack or blame the lawyers, and the passage of this legislation presented yet another opportunity for legislators and media to suggest that it must be good because the lawyers are against it. Once again, however, such charges miss the mark. The State Bar of Texas and many of the metropolitan bars, including the Houston Bar Association, generally supported education reform as well as a revised business tax. By and large, the issues about which lawyers spoke pertained to whether the tax was fair and whether special interest deductions, exemptions, exclusions and exceptions would be permitted. The State Bar and the Houston Bar Association each passed supporting resolutions. At its March meeting, the HBA directors, for example, unanimously passed the following resolution:

The Houston Bar Association is committed to excellence in the public education of Texas children. The Houston Bar Association is committed to ensuring that the funding of that system be fair to all and it encourages the Legislature to treat all businesses and professions equitably and fairly. The Houston Bar Association calls upon other businesses and professions in the state to share this vision and commitment to fairly funding public education in Texas.18

Representatives of the bar, including members of plaintiffs, defense and other lawyer organizations, closely followed the progress of this legislation, and some spoke for or against various features that appeared to disproportionately affect tax paying groups. In short, the principle thrust of the bar’s position was that this tax, which most agreed was necessary and inevitable, should be far reaching and that deductible expenses should be equal and fair and that exceptions, exclusions and exemptions should be avoided or minimized.

Against Whom does the Margin Tax Apply?

The new gross margin tax applies to “taxable entities,”19 defined as partnerships, corporations, banking cor-porations, savings and loan associations, limited liability companies, business trusts, professional associations, business associations, joint ventures (except joint operating or co-ownership arrangements in which the parties elect out of partnership treatment under IRS Code §761(a)), joint stock companies, holding companies or other legal entities.

This tax does not apply to sole proprietorships, general partnerships the direct ownership of which is entirely composed of natural persons, passive entities (as defined), or entities that are exempt from taxation such as non-profit organizations. It does not apply to certain grantor trusts, the estate of natural persons, escrows, qualified family limited partnerships, certain passive investment partnerships, passive trusts, REITs, real estate mortgage investment conduits, and certain qualifying insurance organizations.20 Taxable entities with less than $300,000 in gross revenues are not subject to the tax, and taxable entities will be exempt if their calculated tax liability is less than $1,000.21 Lawyers who practice law in a general partnership of individuals or as a sole proprietorship, however, will not be subject to the new business tax.

How is the Tax Calculated?

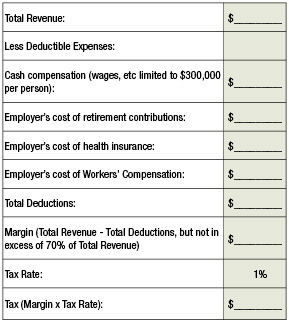

The gross margin tax rate is 1 percent (0.5 percent in the case of retailers and wholesalers). Under Texas Tax Code, Section 171.003, this tax rate may not be increased without voter approval.22 The tax rate is to be applied to a taxpayer’s “taxable margin.” Taxable margin is generally the difference between the taxpayer’s total revenue as reported on his federal income tax return23 and permitted deductions. For those engaged in the manufacture and sale of goods, deductible expenses may include the cost of goods sold. For service companies and those not engaged in the sale of goods, such as law firms, permitted deductions will include “wages and cash compensation” and the cost of employee “benefits.”24 Compensation includes wages and net distributive income from partnerships, limited liability companies and S Corporations paid to natural persons, plus stock awards and stock options. This includes compensation paid to officers, directors, owners and partners. The deduction for wages and cash compensation is capped at $300,000 for any single person. “Benefits” are limited to benefits deductible for federal tax purposes and include such things as health, retirement and worker’s compensation benefits. They do not include social security or Medicare contributions. Benefits are not capped.

A tax calculation for a service organization that earns over $300,000 might look something like this:

Do Lawyers Get Credit for Flow-Through Funds and Pro Bono Services and Expenses?

Yes and no. House Bill 3 outlines a number of items that need not be included in the computation of revenue. They include flow-through funds mandated by law, contract or fiduciary duty to be distributed to a claimant by his attorney or to other entities on behalf of the client. These include damages due the claimant, funds subject to a lien or other contractual obligation arising out of the representation, funds subject to a subrogation interest or another third party claim, and referral or other fees paid to another attorney in the matter who is not a member of the firm.25 It also includes specific reimbursable expenses incurred in the prosecution of a claimant’s case. Finally, an attorney may exclude “out of pocket” expenses incurred in the prosecution of a pro bono matter up to $500. The value of an attorney’s “pro bono” services may not, however, be deducted. Doctors, by comparison, were granted and will receive special credit for revenues derived from Medicare, Medicaid, Children’s Health Insurance Program, workers compensation and military insurance programs.26

When Does the Tax Apply?

The initial tax period will be 2007, and the return for the prior year and the computed tax will be due by May 15, 2008.

Will the 1 Percent Business Tax Rate Likely Increase in the Future?

With the creation of a new business tax in Texas, the legislature anticipated taxpayers’ concern over future tax rate increases. To assure that this was not the top of a slippery slope, the legislature expressly provided that future rate increases would require voter approval.27

Will Business Taxes Paid be Deductible on a Taxpayer’s Federal Income Tax Return?

Like property and franchise taxes in the past, there is no reason to believe that the new business margin tax in Texas will not be deductible on the business entities’ tax return, which means that partners in a partnership, for example, will effectively receive the benefit of this deduction.

What if My Business is not Profitable?

For the constitutional reasons mentioned, net income is not the test against which a tax obligation is measured. Consequently, a business may actually realize a net loss for the tax year and yet still owe the margin tax. This has been identified as one of the inherent objections to this legislation. That is, it is not just assessed against those who can pay.

What Credit Will I Receive on My Real Property Taxes?

Citizens of the state of Texas have long paid some of the highest real property taxes in the nation. Indeed, property tax creep, whether due to increasing rates or rising property values, has made continued home ownership difficult if not impossible for many, particularly the elderly and retired. The stated legislative goal was to roll back school taxes pertaining to maintenance and operations and “put the brakes” on future rate escalations. According to Governor Perry, HB 1 will enable the state to reduce property tax rates in many areas from $1.50 per $100 valuation to $1.00 per $100 valuation (a 33 percent reduction) and will limit future increases to not more than $.04 per year without voter approval.28 Of course, this bill does nothing to limit rapidly rising property values in many areas, so anticipated tax reductions may likely be offset by continuing property value increases.

What are the Anticipated Economic Benefits of This Tax?

At the time he signed the margin tax bill, Governor Perry reported that “employers will benefit with a tax system that is fairer, a tax base that is broader and a tax rate that is substantially lower than the one we have today.” He went on to say that House Bill 3 “rewards employers for creating jobs and investing in employee benefits” and that this bill “protects small employers so that they can continue to drive Texas’ economic growth.” He also pointed out that it “exempts sole proprietors and general partnerships from the tax, as well as businesses whose gross receipts total $300,000 or less, and those whose tax bill is less than $1,000.” And, Governor Perry says that it “rewards employers that create jobs and contribute to our economy.” He did not say, although others remind us, that this bill effects the largest tax increase in Texas history and will place this state among those with the highest business tax in the country.

Conclusion

We have yet to see if this legislation passes constitutional muster, and whether it actually raises the funds required. And, we can only speculate what, if any, tax avoidance measures may be taken by the tax paying public. Clearly, the final chapter is yet to be written

William E. Junell is a 1971 graduate of the University of Texas School of Law. Upon graduation, he joined the firm of Reynolds, Allen & Cook. Seventeen years later, he joined the trial section of Andrews Kurth LLP and in 1997, he became one of the founding members of Schwartz, Junell, Greenberg & Oathout, L.L.P. Junell is a director of the Houston Bar Association.

Endnotes

1. Opinion-Editorial, Carol Keeton Strayhorn, Texas Comptroller, March 28, 2005. 2. Article VIII, ‘1-E states: “No state ad valorem taxes shall be levied upon any property within this state.” 3. 826 S.W.2d 489 (Tex. 1992). 4. Texas Constitution, Article VII, Section 1. 5. 176 S.W.3d 740 (Tex. 2005). 6. Neeley v. West Orange-Cove, 176, S.W.3d 746, 755 (Tex. 2005). 7. Texas Comptroller’s Office: Window on Government (February, 2006). 8. Neeley v. West Orange-Cove, 176 S.W.3d 746, 755-757 (Tex. 2005). 9. Texas Education Code, Section 41.001 (1993). 10. Neeley v. West Orange-Cove, 176 S.W.3d 746 (Tex. 2005). 11. Office of Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts: Texas Revenue History by Source, 1978-2005 12. Chapter 171, Texas Tax Code. 13. Chapter 171, Texas Tax Code. 14. The Report may be viewed at http://www.ttrc.state.tx.us. 15. The bills may be viewed at http://www.capitol.state.tx.us/. 16. Texas Con., article VIII, Section 24(a); Letter of Attorney General Greg Abbott dated April 17, 2006. 17. Opinion-Editorial, Carol Keeton Strayhorn, Texas Comptroller, March 28, 2005. 18. Resolution of the Board of Directors of the Houston Bar Association passed March 28, 2006. 19. See Section 171.0002(a) for the statutory definition of “taxable entities.” 20. Texas Tax Code, Section 171.002 21. Texas Tax Code, Section 171.002(d) 22. Texas Tax Code, Section 171.003 23. See Section 171.1011 24. Texas Tax Code, Section 171.101, 1013 25. Texas Tax Code, Section 171.1011 26. Texas Tax Code, Section 171.1011(n). 27. Texas Tax Code, Section 26.08. 28. Tax Code, Section 26.08.

Text is punctuated without italics.

< BACK TO TOP >

|